Seasonal Connections: Japan’s New Era, Plum Blossoms in Dazaifu, and the Shinto Exhibition at the CMA

Tags for: Seasonal Connections: Japan’s New Era, Plum Blossoms in Dazaifu, and the Shinto Exhibition at the CMA

- Blog Post

- Exhibitions

April 5, 2019

Devotional Shrine with Image of Tenjin Visiting China, 1600s. Textile appliqué by Empress Meishō (1623–1696). Edo period (1615–1868). Lacquered wood, gold powder (maki-e), metal fitting, ink, and textile appliqué (oshi-e); h. 33.5 cm. Sata Tenjingū, Moriguchi, Osaka Prefecture

Shinto: Discovery of the Divine in Japanese Art opens next week at the Cleveland Museum of Art. Ten years in the making, this exhibition — on view only in Cleveland — features a selection of rare works designated by the Japanese government as Important Cultural Properties. The timing of this exhibition coincides with a new era in Japan’s history, the name of which, Reiwa, has connections to the artwork on display in the CMA’s exhibition. Dive deeper into these connections in this essay by the CMA’s curator of Japanese art and curator of the exhibition Shinto: Discovery of the Divine in Japanese Art, Sinéad Vilbar, and check out the exhibition in person beginning Tuesday, April 9.

On Monday, April 1, Japan announced the name of its new era: Reiwa (令和). When the new Japanese emperor ascends to the throne on May 1, the current era, Heisei (平成), ends and the Reiwa era begins. Heisei is said to mean “achieving peace” and is the name of the era associated with the currently reigning emperor, who took the throne in 1989. He is the first emperor in 200 years to abdicate and will do so on April 30. Historically, Japanese era names changed at critical junctures in an emperor’s reign, often to bring a sense of renewal. Now the era name remains the same for the entire reign. In the past, era names were selected from classical Chinese literature. For the first time, the era name has been chosen from classical Japanese literature, specifically the Man’yōshū (A Collection of Myriad Leaves), the oldest existing anthology of Japanese poetry, containing some 4,500 poems on numerous themes by more than 350 known authors.

“It is now the choice month of early spring, the weather is fine, the wind is soft. The plum blossom opens…” — Japanese literature scholar Mack Horton’s translation of part of the preface to the fifth book of the Man’yōshū (A Collection of Myriad Leaves)

Reiwa was taken from the preface of the fifth book of the anthology, which contains poems dating from the year 815 and beyond. The section’s theme centers on the plum flower (also called an apricot flower). According to Japanese literature scholar Mack Horton, the preface reads in translation, “It is now the choice month of early spring, the weather is fine, the wind is soft. The plum blossom opens.” “Choice month” is reigetsu (令月), or the second month of the year, and “soft wind” is kaze odayaka (風和). Another way to translate this is, “in this auspicious early spring month, the air is clean and the breeze is gentle [hatsuharu no reigetsu ni shite kiyoku kaze yawaragi].”

The first character of reigetsu and the second character of kaze odayaka or kaze yawaragi (also read wa) were combined to form Reiwa, which has been given a variety of English glosses but is generally said to connote “pursuing harmony.” The content of the preface draws upon welcoming remarks made by the courtier Otomo no Tabito (655–731) at a gathering he hosted in 730 at his residence in Dazaifu (in contemporary Fukuoka Prefecture in Kyushu). Guests composed and sang their own poems as they admired the plum blossoms flowering in the garden. Otomo is said to have suggested, “with the sky serving as a canopy and the ground as a carpet, we are sitting relaxed and close together and exchanging sake cups. Let us make this ume (plum) garden the subject of the poems we compose.”

Dazaifu is also the site of a famous shrine dedicated to the kami Tenman Tenjin, the posthumously deified spirit of the courtier Sugawara no Michizane (845–903).

Tenjin is strongly associated with the plum. He had a beautiful plum tree outside his home in the ancient capital Heian (now Kyoto), to which he composed a tearful waka poem when he left to travel to Dazaifu to assume a government post in de facto exile. This fraught scene depicting Michizane saying goodbye to his beloved plum is touchingly painted in the second scroll of the 1311 illustrated handscroll set The Illustrated Miraculous Origins of Matsuzaki Tenjin Shrine (Matsuzaki Tenjin engi emaki), on view during the first rotation of the exhibition (April 9–May 19) in the section titled “Gods and Great Houses.”

This set, belonging to Hōfu Tenmangū, an important Tenjin shrine in Yamaguchi Prefecture, is designated as an Important Cultural Property by the Japanese government.

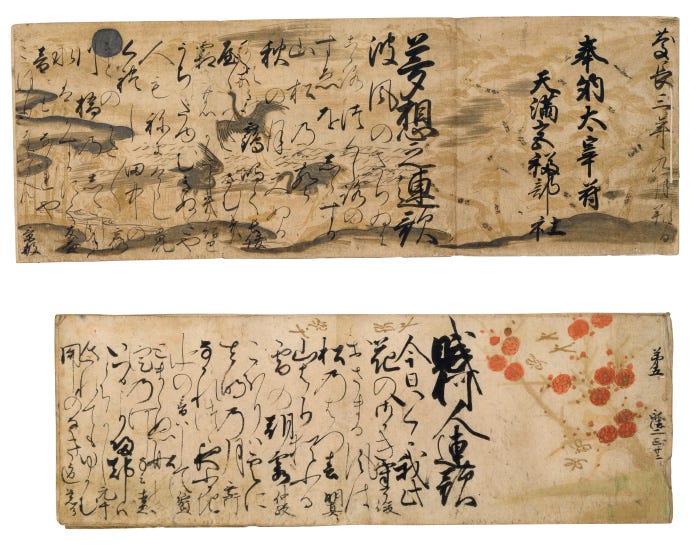

Tenjin’s shrine in Dazaifu is called Dazaifu Tenmangū. This April has been a momentous time for Dazaifu Tenmangū, as its head priest has retired and his son has taken the chief position at the shrine. Shinto: Discovery of the Divine in Japanese Art includes three works from this shrine dedicated to Tenjin over the two rotations that take place during the exhibition. One of the works is the record of a poetry gathering thought to have been held at the shrine in the Nanbokuchō period (1336–1392). Renga, or linked-verse poetry, was composed as a ritual means of honoring Tenjin.

Just as Buddhist monks might read sacred texts called sutras before Buddhist deities as a ceremony, composing poems together before Tenjin was a religious activity.

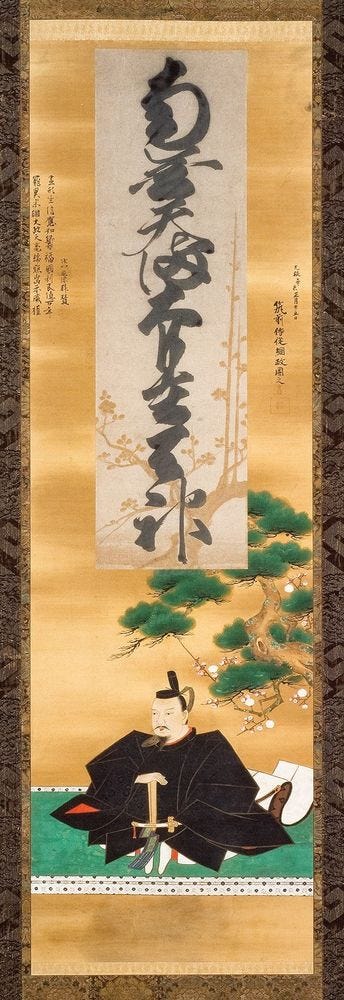

The other work from Dazaifu Tenmangū on view in the exhibition’s first rotation is a marvelous calligraphic rendering of the name of Tenjin by emperor Go-Yōzei (1571–1617) that is affixed to an image of Tenjin painted by a regional leader of Dazaifu.

Tenjin is shown in formal courtly garments seated before a pine tree and a flowering plum tree. Paintings and calligraphies like this one would have been displayed as the presiding icon over poetry gatherings offered to Tenjin.

May we all be hardy like the plum blossom, the first flower to bloom after a cold winter!