A Hunt for Meaning: Hunting Scenes in India, 1700–1900

- Blog Post

- Exhibitions

Articulated in seductive colors with intriguing details, hunting scenes in paintings from India celebrate more than the coup de grâce. In the startlingly expansive scenes created during the 1700s and 1800s at the court of Udaipur in southern Rajasthan, the tense and thrilling moments — often laced with extreme danger — leading up to the kill are shown minute by minute. Several of these magnificent hunt scenes form a crucial part of the special exhibition A Splendid Land: Paintings from Royal Udaipur, along with depictions of pleasure palaces, festivals, temples, and monsoon-drenched landscapes. How are visitors to understand such rousing and often violent depictions of hunting, when many are probably familiar with tenets of nonviolence associated with Buddhism, Gandhian ideology, and yoga practices that also have roots in India? In this short discussion of seven images of hunting on view at the Cleveland Museum of Art this summer, multiple contexts and layers of meanings emerge.

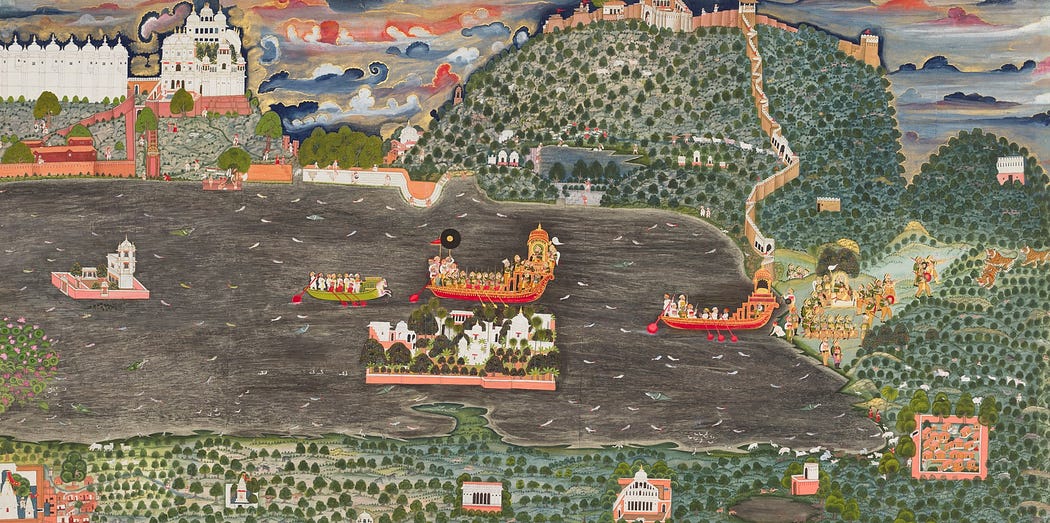

The opening painting in A Splendid Land shows the reigning monarch, called Maharana (Great King) in Udaipur, fulfilling his royal imperative: to enjoy and protect the land over which he reigns (fig. 1). Under the rosy gold light of dawn, the king Sangram Singh II (reigned 1710–34), with a halo of divine sanction behind his head, sits in the elevated pavilion of his royal boat, surveying his gleaming City Palace in the distance as he sails past his Lake Garden Palace. Temples at the lower left indicate divine presence in Udaipur. The lake teems with aquatic life, and the surrounding forests bustle with deer, rabbit, boar, cows, big cats, birds, and residents stirring to start their day. Sunrise in Udaipur presents the long-held Indian connection between the health and abundant productivity of the land with the righteousness of the ruler.

At the far right of Sunrise in Udaipur, the king is shown a second time. Having disembarked, he sits under a pair of mango trees directing his son, the prince Jagat Singh II, to shoot a tiger. According to the inscription on the back, the tiger had been spotted by one of the nobles, who asked that the royal party come to that place.1 The inscription states explicitly that when the tiger was “eight hands” away from the prince, he shot her in the forehead and “stopped her.” What ensued was a grand celebration at the palace at which sumptuous gifts of cash, elephants, caparisoned horses, food, and other items were presented to the court. The celebration is not shown, but it commemorated the courage and skill of the prince on a glorious morning that led to bonding among the nobles and resulted in gifts that increased the power and prestige of the court.

Hunting was not always such a clean, glowingly thrilling affair. At times it was horrifyingly dangerous to men and beasts alike. In a painting of a hunt taking place at night, illuminated by men wielding and tossing firebrands, Jagat Singh II (reigned 1734–51), now king, shoots a leopard (fig. 2). According to the inscription on the back, the leopard killed a man, who is probably the one being mauled in the tree. Boar, deer, bear, foxes, and rabbits leap in confusion and panic; some fall dead.

The rulers of Udaipur, like those of other neighboring kingdoms whose territories mainly fall in the present-day state of Rajasthan, belong to hereditary families of Hindu warriors known as Rajputs. Organized hunts such as those depicted in the paintings were the prerogative of the king. In the painting of Jagat Singh II hunting, the king’s men had created a bounded space into which the animals were funneled toward the elevated, camouflaged structure where the king and four nobles, each identified by name in the inscription, wait with their guns. This technique is related to hunting practices employed by the Mughal emperors, who ruled over the Rajputs throughout most of the 1600s, to solidify the hierarchy of nobles allowed to hunt with them, which mirrored hierarchies at court.2 This type of hunt with a variety of animals driven into an enclosure functioned to proclaim the supremacy of the sovereign hunter over all beasts — and analogously over all subjects — as a “violent and visible spectacle of political authority.”3 The family name of the Udaipur kings, Singh, means lion. As the lion among men, the king is the victorious match of the king of beasts. Drums and massive horns publicly proclaim to the realm his power and ability to protect the land.4 The artist created this painting as a gift to Jagat Singh II, memorializing the intensity of that night and the fulfillment of his duty as ruler.

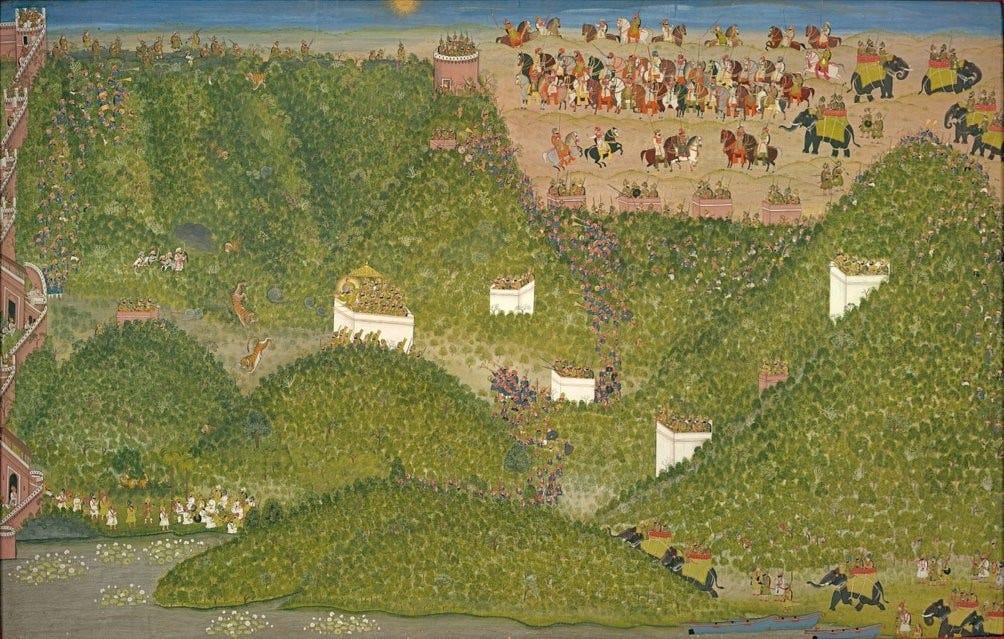

Large-scale organized hunts also functioned as rehearsal for battle. Rajput rulers were responsible for repelling enemy attacks on their kingdoms. Maharana Swarup Singh (reigned 1842–61), with the green halo on the foremost elephant, invited allies to join a hunting expedition on a winter morning in the ancestral hunting grounds called Nahar Magra (fig. 3). They practiced mobilizing encampments and navigating camels and elephants over challenging terrain described as “an inextricable network of ravines . . . entirely covered with a thick underwood of thorny dwarf acacias,” in pursuit of boar, considered by the Udaipur kings to be the most formidable and desired game.5 Closer to the city, in a public display of military prowess and organizational skill, the tiger among men, Jawan Singh (reigned 1828–38), from atop a hunting tower, shoots a magnificent tiger shown ambling vertically from the hilltop ridge down to his final resting place by the shore of the lake (fig. 4). By the mid-1800s, the British were beginning to exercise political and economic control over the rulers of Udaipur, and paintings such as figures 3 and 4 were made to flex the image of their continued power in the face of a new threat.

The rulers of Udaipur trace their genealogical descent from the divine hero Rama, who was a warrior and a hunter, as well as a human incarnation of the Hindu god Vishnu. Victorious over his enemies, Rama supported his wife and brother during their years of exile in the forest, and he used his weapon of choice, the bow and arrow, to both hunt and fight. On display in the gallery of Indian paintings from the permanent collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art are works pertaining to the story of Rama. In figure 5, Rama and his wife sit on a deerskin and watch his brother Lakshmana roast meat over an open fire, a leaf platter covered with freshly dressed venison by his side. Over Lakshmana’s left shoulder is the skin of a leopard, and over the lap of Rama’s wife is the skin of a black buck, all acquired through skillful hunting. The figure of Rama embodies the quintessential righteous ruler, an able hunter who is victorious against forces of disorder and who maintains balance in nature and society. He is the model for his scions, the kings of Udaipur.

Paintings made for Rajput rulers of other kingdoms also depict the royal hunt as essential among activities of the court. Tiger hunt of Ram Singh II was made in the kingdom of Kota, about 250 miles northeast of Udaipur. The artist placed a golden tiger as the central image, larger than life, dramatically offset by the purple cliffs in the background (fig. 6). The more magnificent the tiger, the more powerful the king who bests her. The nobles are arranged in a studied hierarchy; musicians proclaim the act to the world; women gaze on in rapt admiration.

With British colonial presence in India, beginning officially in 1858, controls began to be placed on hunting. For centuries, Rajput families had managed a form of predatory care that ensured their stocks of game did not get depleted. Under British rule, however, hunting practices were expanded, with mainly British sportsmen hunting animal populations — especially tiger — to near extinction. By the 1880s, in an effort to curb extinction, hunting was legally restricted to areas reserved for British officers and licensed huntsmen.6 The colonial government acquired and repurposed ancient hunting grounds, despite protest from the royal families. Documents recording land negotiations reveal that the royal families preferred the reinstatement of their ancestral hunting grounds to generous cash remuneration, such was the symbolic importance of the royal hunt to the identity of the Rajputs.7

An exhibition dedicated to the art and times of Indian photographer Raja Deen Dayal (1844–1905), on view at the Cleveland Museum of Art until August 13, 2023, includes a photograph of the commander in chief of the British Indian Army, Field Marshal Frederick Roberts (1832–1914), seated among his circle of family and friends (fig. 7). At the right is a tiger-skin rug, being stepped upon by an unidentified sitter. The British elite in India wished to communicate their benevolent civilizing control over the Indian kings, who, like tigers, could be dangerous, violent, and, in their view, bestial. They projected the image of being protectors of the people, protecting them from their own kings, and worked to undermine the authority of the regional rulers throughout India. One way of doing so was by eliminating the tiger population and the hunting grounds that were symbolically linked to Rajput royal status.

Hunting scenes in Rajput paintings were created for the ruling elite, hereditary warriors whose worldview and sets of expectations and assumptions differ fundamentally from those of most American museumgoers today. Viewed from the perspective of a Rajput ethos, hunting was an essential component of righteous rule on a number of levels. Organized hunts kept them and their allies ever ready to confront invading forces; hunts created situations of real danger in which allegiances could be tested, and the king could demonstrate his supreme skill and unflappable courage. As public spectacles, royal hunts were a means of assuring the population that their king is virile and capable of protecting them. In this way, rulers displayed the ideal characteristics of descendants from the divine hero Rama. Moreover, as paintings from the Udaipur court reveal, hunting allowed the ruler to take pleasure in the land, to enjoy adventurous camaraderie with his closest companions, and to see firsthand the condition of the realm, the people, and the animals. Hunting connotes abundance, supported by the water resources that the Udaipur rulers assiduously engineered and maintained in order to ensure the preservation of the kingdom’s bounty and promote the balance and pleasure it entails.

A Splendid Land: Paintings from Royal Udaipur is organized by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art in collaboration with the City Palace Museum, Udaipur, administered by the Maharana of Mewar Charitable Foundation. This exhibition has been co-curated by Debra Diamond, the Elizabeth Moynihan Curator for South Asian and Southeast Asian Art at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art, and Dipti Khera, Associate Professor, Department of Art History and Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. It is on view at the Cleveland Museum of Art from June 11 to September 10, 2023.

[1] Debra Diamond and Dipti Khera, A Splendid Land: Paintings from Royal Udaipur, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution; Munich: Hirmer Publishers, 2022), 323–24.

[2] Anand S. Pandian, “Predatory Care: The Imperial Hunt in Mughal and British India,” Journal of Historical Sociology 14 (2001): 97.

[3] Pandian, “Predatory Care,” 80.

[4] For the role of sound in the hunt, see Richard David Williams, “Music for Hunting: Animals, Aesthetics, and Adivasis in Rajput Culture,” in Early Modern Literary Cultures in North India — Current Research, ed. Imre Bangha and Danuta Stasik (New York: Oxford University Press), forthcoming.

[5] Diamond and Khera, A Splendid Land, 375nn2–3.

[6] Pandian, “Predatory Care,” 83.

[7] Julie E. Hughes, Animal Kingdoms: Hunting, the Environment, and Power in the Indian Princely States (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013), 40–41.