Geese and Reeds: Finding Our Place in the Family of Things

- Blog Post

- Collection

- Education

%20(detail).webp&w=1920&q=75)

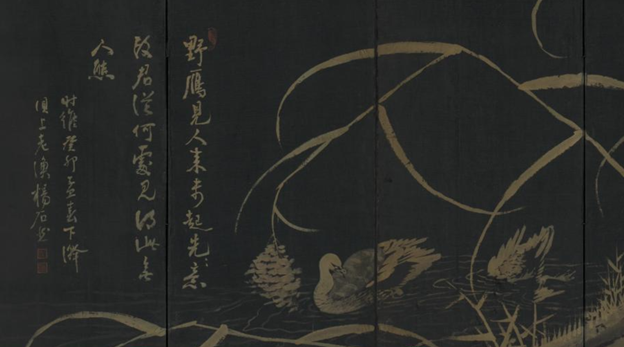

Geese and Reeds (노안도) (detail), 1903. Yang Gi-hun (양기훈). (Korean, 1843–1919?). Ten-panel folding screen; gold pigment on purple silk; painting: 140.6 x 328 cm. Private collection, 3.2019

In this essay, Audrey combines the descriptive and interpretive writing skills she learned during her summer fellowship with a poem to create a visual analysis of an artwork in the CMA’s collection.

When people reflect on their high school years, the first thing that comes to mind is not typically the required reading; however, some of the classic novels, plays, and poems I was introduced to during that time were highly impactful to my development as a young adult. As I wandered through the Cleveland Museum of Art’s Asian art galleries, I was captivated by a 10-panel folding screen, titled Geese and Reeds (노안도), by Korean artist Yang Gi-hun. The jubilant birds soaring boundlessly across the rich indigo-dyed silk reminded me of a poem I discovered in high school.

Mary Oliver (opens in a new tab)’s, “Wild Geese” begins with these lines:

“You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles in the desert repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.”

These words offer comfort and guidance to those plagued by the stress of expectations and perfectionism.

Similarly, when viewing Geese and Reeds, I see the will to appear flawless in Yang’s careful detail work, which manifests each avian feather in precise streaks of gold ink. About half of the geese depicted on the panel are rooted on the riverbank, many looking up longingly at the creatures in flight above them. Their webbed feet appear steady on the soil, but there is a sense of yearning, as their graceful necks crane upward. While two mischievous birds venture into the water, the rest joyfully swoop through the air. Oliver’s affirmation that one must simply “love what it loves” can be seen in the geese taking full advantage of their aerodynamic wings and reveling in the freedom of flight.

In the painting’s lower left corner, the fluid strokes of Yang’s written characters are reminiscent of the curved reeds that dip in the gentle breeze. That inscription reads, “Seeing people approaching, wild geese are getting ready to fly. Where did they learn such wisdom, which people these days no longer possess?” The artist admired the birds, who know their place in the world and use their strengths as small but autonomous creatures. Yang also emphasized the way in which humans have lost the self-determination that comes so easily to the geese. As a complement to those sentiments, Oliver’s poem continues with expressions about the feebleness of human preoccupation amid a resilient natural world:

“Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.

Meanwhile the world goes on.

Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain

are moving across the landscapes,

over the prairies and the deep trees,

the mountains and the rivers.

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again.”

Oliver’s description of the biosphere’s continuity despite human endeavors is exemplified in the contrast between the prosperous ecosystem captured in Yang’s painting of earthly beauty — with its depection of “wild geese,” perhapse landing at the bank of their winter home or leaving as winter turns to spring — and its inscription that suggests humanity has lost the wisdom the natural world offers.

The geese and reeds theme has innate meaning and significance in Korean art. Written in hanja (opens in a new tab), which is the traditional writing system consisting mainly of Chinese characters, the word “reed” is a homophone for “old man,” pronounced no. Likewise, “geese,” pronounced ahn, is the equivalent of “comfort.” Together, the phrase “reeds and geese,” pronounced noahn, means “aging peacefully.” In turn, artworks with geese and reed imagery were often gifted during birthdays or retirement ceremonies, to wish others well in the time to come. Similarly, as the poem articulates, Oliver embraced the inner peace found with personal growth.

The flying geese of the silk panel remind me of the joys of life. We, as people, have the potential to regain the lost wisdom Yang lamented, to connect with ourselves through a less critical lens. The widespread wings of the birds symbolize the potential to find liberation, escaping the weight of anxiety and the burden of trivial stressors. The geese on the riverbank need only spread their wings to fly; likewise, we should contemplate the barriers that hold us back from becoming the best versions of ourselves. Oliver, too, offered words of hope in the poem’s final lines, leaving us with the power to grow and age at peace with who we are:

“Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting—

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.”

View this intricate panel along with several other Korean artworks in Interpretation of Materiality: Gold located in gallery 236.

Originally from North Dakota, Audrey Chan is a junior at Colgate University in Hamilton, New York. Her studies align with her passion for the arts as an art history major, with minors in museum studies and anthropology. She is involved in music and dance organizations on campus, including the Colgate Raider Pep Band, the Colgate University Orchestra, the Colgate Tap Troupe, and the Colgate Ballroom Dancers. Chan plans to pursue graduate and doctoral studies upon graduation and aspires to work in the museum field.