Facing the Ancestors: Conserving a Chinese Ancestor Group Portrait

Tags for: Facing the Ancestors: Conserving a Chinese Ancestor Group Portrait

- Blog Post

- Conservation

CMA Staff

September 27, 2019

Now on view in the Chinese Paintings and Calligraphy Gallery, visitors can see a new installation titled Facing the Ancestors: Chinese Portrait and Figure Painting which features a recently conserved Chinese ancestor group portrait.

On view through February 8, 2020, the new installation celebrates both the gift and the painting’s successful remounting into a Chinese-style hanging scroll. Shortly after its arrival at the museum last year, the artwork underwent treatment in the museum’s June and Simon K. C. Li Center for Chinese Painting Conservation, as outlined in the video below.

This video captures and explains the complex conservation process required to restore and remount this painting.

In the discussion below, Clarissa von Spee, Chair of Asian Art and James and Donna Reid Curator of Chinese Art, and Yi-Hsia Hsiao, Associate Conservator of Chinese Paintings, discuss the painting and the conservation process.

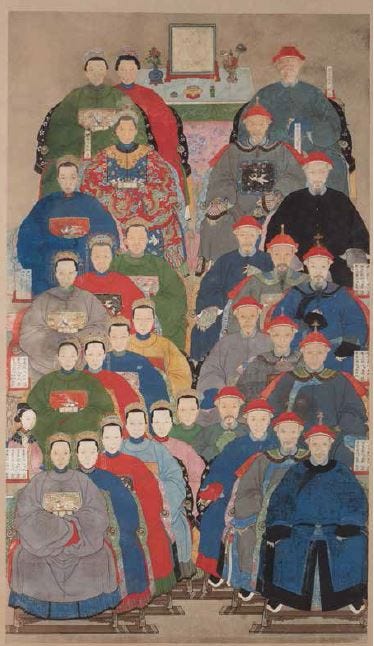

Clarissa von Spee: We are looking at an oversized Chinese Qing dynasty ancestor group portrait. In the standard frontal orientation of ancestor portraits, this scroll features six generations and is read from top to bottom, with men on the right and women on the left. Because husbands could have several wives, there are 13 men and 17 women accompanied by a female servant. Inscribed tablets note their rank and relation within the family; the bottom row contains the most recent generation, while the figure on the far right may have commissioned the painting. Square badges on the chests of court robes indicate a sitter’s rank as an official; wives would wear the same badge. Out of reverence, the clan’s descendants probably erased the family name on the scroll before it went on the art market. Scrolls of this type were hung over the home altar for worship during the New Year celebrations.

Yi-Hsia Hsiao: This painting required extensive conservation treatment before it could go on view. First, we did an initial condition assessment of the painting in the frame. Then we disassembled the frame for a closer examination of the painting. Framed under plexiglass, the painting was in poor condition and mounted in a panel format when it arrived at the museum.

Clarissa: We discussed the painting’s condition in order to determine the format in which the painting would be displayed. This initial assessment led to the decision to replace the old paper linings and fills and remount the painting in the traditional Chinese hanging scroll format.

Yi-Hsia: Executed with Chinese ink and colors on xuan paper, the work displayed creases, losses through flaking, scratches, foxing, yellowing, and accretions throughout. Inactive white mold was present in the painting’s upper right corner. Additionally, an entire bunch of flowers and the hair ornaments of the two female figures at the upper left were so poorly inpainted that their style did not match the original.

Clarissa: Visitors can see a comparison of the old inpainting of the two crowns and flowers done in freehand brushwork style with the new inpainting done by Yi-Hsia in the more exact brushwork style in the video.

Yi-Hsia: After the painting’s surface was gently cleaned and washed with warm water using a goat-hair brush, the old paper linings were removed. New linings of soft, thin, toned xuan paper were applied according to traditional Chinese mounting methods. Numerous samples of the headdress ornaments and the camellia flower, often depicted in Chinese ancestor portraits, were painted on slips of sized paper before applying the best match to an area where the original paper and painting had been lost. Then the painting was spread on a drying board to flatten and even out the paper linings and patches and left to dry for one year.

Clarissa: The transformation of the painting, from before treatment to after treatment, is remarkable to see.

Yi-Hsia: Retouching and inpainting areas of loss is controversial, and Western and Eastern approaches in conservation differ: the former leaves missing areas largely untouched but in a neutral tone, while the latter keeps painted areas intact and repaints them. The new method applied here is fully reversible and was developed to find a compromise between the two traditions. Senior conservator Pingfang Zhu at the Shanghai Museum was a valuable collaborator for this undertaking.

Check out the conserved group portrait on view NOW at the CMA.