Close Looking with the CMA’s Student Guide Program: Get to Know Raven Navarro

- Blog Post

- Education

- Events and Programs

The Cleveland Museum of Art’s Student Guide Program trains college students to personally engage museumgoers using close-looking techniques. Through this tour-based program, the students aim to demonstrate how works of art from every period and culture from around the world are relevant to how we see, think, and live. The program is generously supported by the Walton Family Foundation and the Ford Foundation through the Diversifying Art Museum Leadership Initiative (DAMLI).

In this recurring series, The Thinker is showcasing CMA student guides, including interviews conducted by one of their peers and short essays focusing on an object of their choosing from the CMA’s permanent collection that exemplifies the ways slow and close looking have impacted their experiences as both a guide and viewer.

Last month we featured an interview with and an essay by computer science major Thomas Ciardi (Case Western Reserve University class of 2021) on Nataraja, Shiva as the Lord of Dance, a must CMA highlight from the museum’s Indian and Southeast Asian art collection. This month we present an interview with Raven Navarro (Cleveland State University class of 2022), who joined the student guide program in fall 2019, and Hannah Boylan (Case Western Reserve University class of 2020). Navarro’s essay, focused on a must CMA artwork from the museum’s Impressionist collection, Claude Monet’s Water Lilies (Agapanthus), is also featured.

HB: How has slow/close looking changed your experience of art?

RN: It has helped me immerse myself in works of art and discover things I had passed over before. That’s what close looking is: diving into works of art, unearthing all there is to find, perhaps even forming a connection. Museums can come off as intimidating to some people because there are artworks they don’t like and/or don’t get. That’s where slow looking would come in — take that fear and stress and turn it into familiarity and comfort.

HB: How do you bring your background and experience to your work as a student guide? How does it feel to work in such a diverse group of students?

RN: My background consisted of the knowledge I gained through my collegiate-level courses, along with the passion engendered by years spent admiring the great artistic masters. So I brought those two things into my work by turning ambition and education into something I could pass along. It is not enjoyable to love something, know so much about it, and then not be able to share that with the people around me.

It is excellent to work with people of all academic and cultural backgrounds. It makes the program that much better because each one of us has something to contribute to the group. We can help each other grow from our different perspectives in both art and life in general.

HB: What is the most challenging part of the program? Most rewarding?

RN: The most challenging part of the program is time management. My schedule is full, but that has also become a rewarding part of this program. When I accomplish my goals within student guiding and outside of it, this excitement overcomes me, making me feel satisfied and complete.

HB: How do you feel that you contribute to the CMA’s mission?

RN: I am here to break barriers, to help others break barriers — to teach and guide them to become more comfortable within every museum’s walls. The museum strives to create transformative experiences through art, “for the benefit of all the people forever,” as its mission states. I feel like I am doing just that each day I come in, with each close-looking tour I lead.

HB: How did your involvement and participation fit into your broader goals for developing yourself?

RN: My broader goal is simple: become a renowned curator. My involvement and participation in this program will help me build the analytical, public-speaking, and team-building skills necessary to reach that life goal. To do so, I also must understand how to share my passion with others in ways that will encourage them to fall in love with works of art in their own manner. I’m learning how to do that here.

HB: Why is slow looking an important (or, dare I say, enjoyable) skill today?

RN: Our society and my generation have become one with instant gratification. Slow looking breaks people out of that mind-set and teaches them that just observing a work of art for 10 seconds longer than usual, a minute longer, even five minutes longer, will give them a stronger and more nourishing gratification. That’s what makes it essential. Yes, you can say you have seen the work, but have you experienced it?

This interview was conducted by CMA Student Guide Hannah Boylan (Case Western Reserve University class of 2020).

Looking Closely at Claude Monet’s Water Lilies (Agapanthus), c. 1915–26

By Raven Navarro, CMA student guide

Location: Nancy F. and Joseph P. Keithley Gallery of Impressionist & Post-Impressionist Art (222)

Museums can be overwhelming; with so many works on display, each visit can feel like a race against the clock. That feeling may cause you as a museumgoer to spend less time looking at an artwork than you otherwise might. But what if you lingered? What might you see and learn if you spent 10 minutes gazing instead of 10 seconds? Slow looking is an approach based on the idea that if you want to get to know a work of art, you need to spend time with it. It’s about allowing yourself space to make new discoveries.

I have overlooked Claude Monet’s Water Lilies (Agapanthus) for almost a decade. I would think, “Okay, Monet, the leader of French Impressionism, the infamous work Water Lilies.” However, when I decided to take 10 minutes and lose myself in the waves of blue, violet, and green on the canvas, I saw much more than lilies alone. What follows is a journaled account of my experience of Monet’s masterpiece using techniques of slow and close looking that I’ve learned in my training as a student guide.

I start by sitting on the bench, placed perfectly in front of this quintessential Monet work, and I stare. I have never done this before, and I find myself wanting to be overtaken by each brushstroke. After scanning every inch of this painting that is twice my size, I need to see it up close. As I approach the canvas, I notice a light source coming from somewhere beyond the upper boundaries of the composition, illuminating the swirls of lilies. The thinly applied paint lends the overall image a smoother look, giving order to what seems like a chaos of brushstrokes. My eyes are drawn to the grouping of lilies near the top, making it the focal point of the image for me. When my eyes finally break free, they drop straight to the bottom of the composition. I’m taken aback when I see the rough strokes of paint in sharp contrast to the still water depicted above. I take a couple steps back to look over these sudden changes and try to analyze what could be happening in the lower portion of the scene. Is it a continuation of the lilies above? Is it grass on the water’s edge? I decide it’s both and take note that, although it surprised me up close, the shift from smooth to rough seen from afar flows perfectly — just as each lily must have been doing as Monet painted his beloved garden pond a century ago.

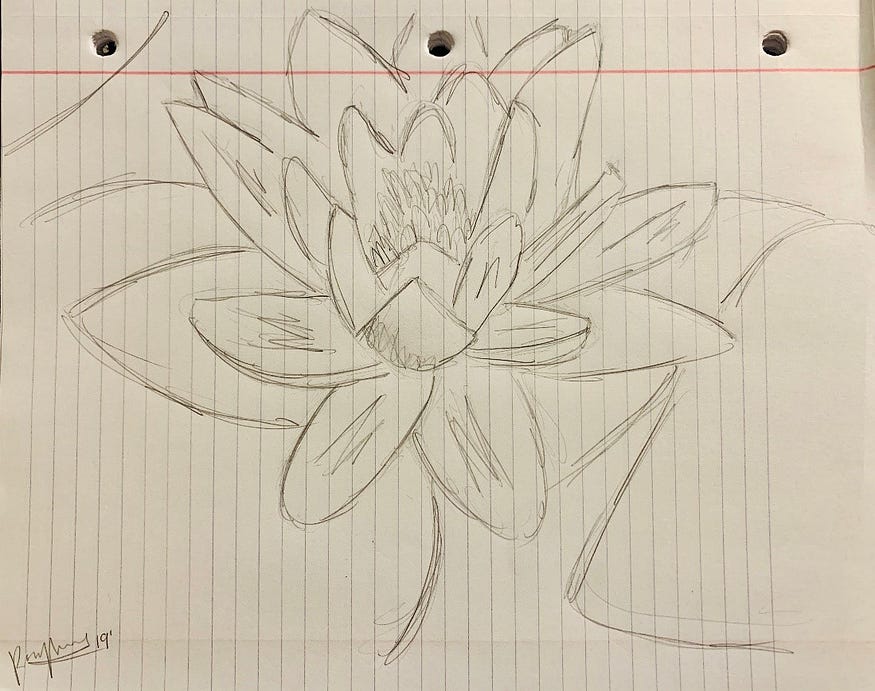

In my last few minutes, I sit down with a piece of paper and a pencil and draw what I think a water lily looks like. I imagine Monet standing at the canvas mixing colors, gathering up a thin layer of paint onto the brush, and slowly laying it down onto the canvas. As I doodle, I wonder what must have been running through his mind at that moment.

My hope in describing this exercise is that it inspires you to slow down and look closely at all that an artwork has to offer, because the rewards are many. If I hadn’t stopped to visually and mentally absorb this work of art, I wouldn’t have had the opportunity to experience it in such a profound way. The important thing is to find a work that draws you in; whether it intrigues or frustrates you, try to view the gallery as a menu to choose from instead of a to-do list. There are so many ways to connect with art. Creating a drawing inspired by what you see is just one of the many options in the close-looking tool kit.

Student-guided close-looking tours — free and open to the public — occur every second, third, and fourth Friday of the academic year at 6:00 and 7:00 p.m. Spring tours begin Friday, January 24, 2020. Student-guided tours offer a completely new way of connecting with the collection in fun, active, and informal ways. Participants are encouraged through discussion, writing, and drawing activities to consider what they see and why they see it as such; the tours are less about the specific histories of artworks and more about building and expanding one’s observation skills.