Clarence H. White's World

- Magazine Article

- Exhibitions

A new retrospective focuses on the work of a leading Pictorialist

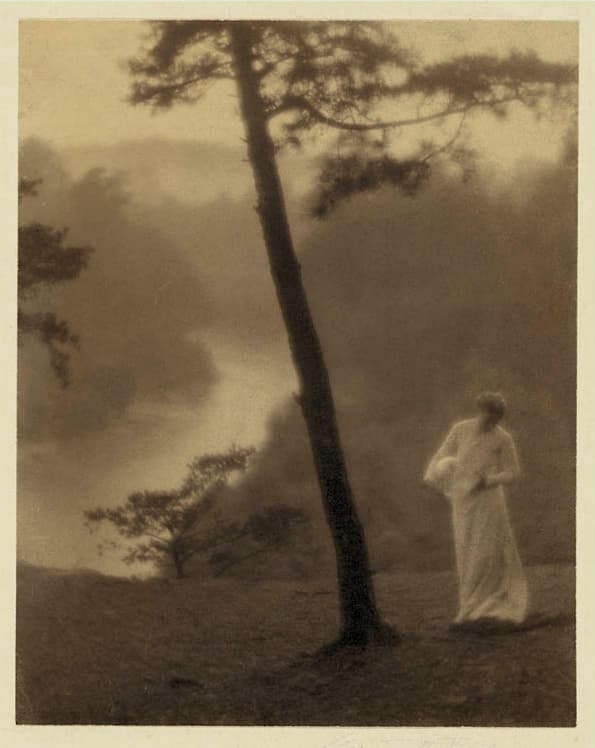

Morning, 1905. Clarence H. White (American, 1871–1925). Gum bichromate print; 24.5 x 19.5 cm. Princeton University Art Museum, The Clarence H. White Collection, assembled and organized by Professor Clarence H. White Jr., and given in memory of Lewis F. White, Dr. Maynard P. White Sr., and Clarence H. White Jr., the sons of Clarence H. White Sr. and Jane Felix White, x1983-515

Ohio native Clarence H. White was an inventive artist, an influential leader of the American Pictorialist movement, a pioneer in the development of photographic magazine illustration and advertising, and founder of the first school of fine art photography in the United States. Yet history has marginalized him, perhaps because his death in middle age left many artistic and professional goals unrealized. Clarence H. White and His World, the first retrospective devoted to the artist in more than a generation, helps redress this lack of attention, surveying White’s career from its beginnings in 1895 to his death in 1925.

Raised in Newark, Ohio, White worked there as a bookkeeper in a downtown wholesale grocery next to the Ohio and Erie Canal. In 1893, White took up photography. A serious amateur from the start, he enlisted friends and family members to pose before and after his workday, often subjecting them to lengthy sessions in the dim light of dawn or dusk. His carefully staged, idyllic depictions of domestic life soon earned national, then international, acclaim. White became a prominent proponent of Pictorialism.

The first concerted effort to elevate the medium from a trade or hobby to the status of fine art, Pictorialism became the standard-bearer for photography as personal expression. The widespread movement was eventually associated with soft-focus, harmonious, and often staged compositions.

Hand manipulation of negatives and prints was an important practice for Pictorialists, who espoused handmade, artisanal prints as a counterpoint to the increasingly industrial nature of photography in the Kodak era, when “snapshooters” were told, “You press the button, we do the rest.” The Pictorialists shared with the older international Arts and Crafts movement the belief that producing and living among well-designed, handcrafted goods and art objects benefited individuals and society as a whole.

Morning (1905) is emblematic of White’s idealized, ennobling creations. The hazy, quiet scene was shot not far from Newark on a hill above the Licking River. Silhouetted, a leaning tree bisects the picture and becomes a flat, and flattening, compositional device reminiscent of those found in Japanese woodblock prints, an art form White admired. The trunk serves as a fulcrum that balances near and far: White’s wife, Jane, stands in the foreground on the right, while the curve of the distant river fills the left side of the picture. Attired in a flowing gown suggestive of an earlier era, Jane gazes down at the glass orb she holds. Is the globe an allusion borrowed from Renaissance and Baroque paintings to suggest the earth, Christian faith, or the transience of human life? Is it a symbol of geometric perfection or of mysteries beyond human understanding? The picture eschews factual truths about American life in the first years of the 20th century, from Jane’s daily life of scrubbing, cooking, and raising two boys to the growing pains experienced by a country beset by labor unrest in an era of rapid urbanization and industrialization. This peaceful image projects White’s personal vision of harmony and union between humans and nature.

Soulful images like Morning garnered praise and awards, but little income; an active market for fine art photography would not form until the 1970s. When White quit his bookkeeping job in 1904 to devote himself fully to photography, he eked out a meager living by producing portraits and illustrations for stories and essays in books and magazines. In 1906 he moved to New York and the following year, to supplement his income, began teaching photography at Teachers College of Columbia University. In 1910 White founded a summer school, and in 1914 he opened a year-round school of photography in New York. Teaching became his primary activity. White School students, working with many instructors, had to master a wide variety of photographic processes and printing techniques and were given open-ended assignments that could be applied to both commercial and fine arts prints. As a teacher and mentor, White inspired a generation of commercial, documentary, and art photographers, including Margaret Bourke-White, Doris Ulmann, Ralph Steiner, Paul Outerbridge, and Karl Struss.

On a student trip to Mexico City in 1925, White died of an aortic aneurysm at age 54. His many contributions to the art of photography came at the cost of personal sacrifices. Fellow photographer Alvin Langdon Coburn understood this and offered praise. “To be a true artist in photography,” Coburn said in his eulogy, “one must also be an artist in life, and Clarence H. White was such an artist.”

Cleveland Art, September/October 2018