Atelier 17

- Magazine Article

- Exhibitions

The influential printmaking studio encouraged spontaneity and improvisation

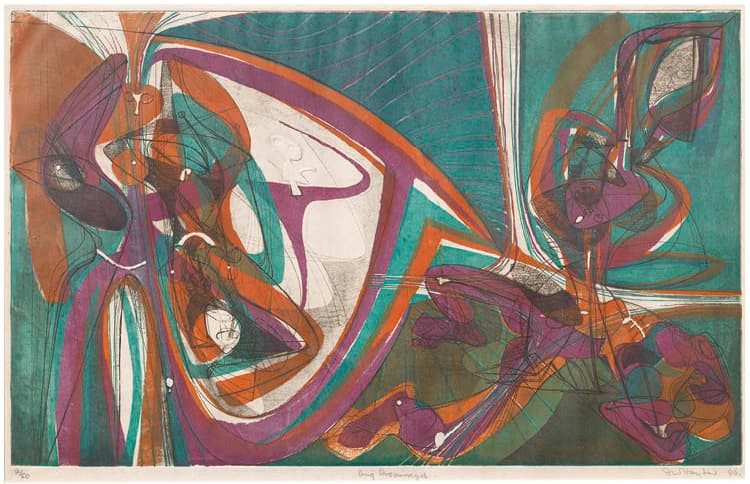

Cinq personnages,1946. Stanley William Hayter (British, 1901–1988). Engraving and etching; 37.6 x 60 cm. Promised gift from a private collection, Cleveland. © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Drawn from the holdings of the Cleveland Museum of Art and local collectors, Cutting Edge: Modern Prints from Atelier 17 showcases approximately 50 works from the influential avant-garde studio. Indeed, no other workshop was more important for the development of modern printmaking than Atelier 17. Founded in 1927 by former chemist Stanley William Hayter, it operated for several decades as a creative laboratory where hundreds of artists eagerly explored and unselfishly shared new discoveries. Among the myriad techniques developed at Atelier 17 were novel ways to execute multicolor printing and generate unusual textured patterns from unconventional materials. Attendees worked independently but could also enroll in courses to learn specific processes. Although no particular artistic style was proscribed, participants were encouraged to emphasize spontaneity and improvisation instead of rigid preconception. “This workshop is an experimental shop,” Hayter explained. “People who come here are people whose curiosity is to find new methods. . . . This is not a school of art; each pursues his own necessity.”

British by birth, Hayter immigrated to Paris during the 1920s and established the first iteration of Atelier 17, named for its principal address at 17 rue Campagne-Première. During the upheavals of World War II, the studio relocated to New York, where it attracted an exciting mix of émigré European Surrealists and American members of the emergent movement of Abstract Expressionism. In 1950, Atelier 17 was reestablished in Paris, further enticing new generations of international artists. The studio operated until Hayter’s death in 1988.

One highlight in Cutting Edge is Hayter’s Cinq personnages from 1946, a powerful print that pre-sents a group of four abstracted figures writhing in agony around a small white wraith floating in space. Hayter undertook the work to commemorate the death of his teenage son from tuberculosis, and his emotional catharsis fostered a technical breakthrough. A milestone in the history of printmaking, it is the first large-scale composition made by applying multiple colors—in this instance, orange, green, and red-violet—to a single plate and printing them simultaneously with one pass through the press, instead of the customary method of printing each color separately from multiple plates. The skillful balance of color separation and blending was controlled by judiciously exploiting the transparencies and viscosities of each ink, for which the artist’s background in chemistry proved essential. Hayter publicized his achievement by devoting an entire chapter to the print’s production in his influential handbook, New Ways of Gravure, published in 1949. As a result, artists around the world studied and adopted the process.

Looking to expand the traditional boundaries of printmaking, artists at Atelier 17 rediscovered the arcane and notoriously difficult technique of printing on plaster. In this procedure, an etched and inked printing plate is covered with wet plaster and painstakingly removed after the material hardens. John Ferren, an artist studying at the Paris studio during the 1930s, created a substantial body of work in this vein. As is the case with his Untiled, No. 12, the resultant printed design was further augmented by delicately carving and painting the plaster to yield a unique relief sculpture. Interestingly, Ferren drew arrows on the back of this work, indicating it should be illuminated from the right in order to optimize the visual effects of its varied surfaces.

A significant percentage of Atelier 17 attendees were women, and the workshop provided an important place for networking and support. A case in point is the Ohio-born Worden Day, who enjoyed a long association with Atelier 17 first in New York and later in Paris. During the early 1950s the studio hired Day to give lessons in color woodcut, thereby launching her teaching career. Her exceedingly imaginative prints inspired by nature, such as Terra Incognita, rank among the most inventive of the era. Here, multiple printmaking processes are evident, including black lines made by engraving and blue areas created by a method of stenciling. Most unusual is the pink-brown background, manifest by inking a scrap piece of wood the artist scavenged.

The legacy of Atelier 17 remains remarkably far reaching. Several key artists who worked at the studio went on to teach in university printmaking departments, thereby promulgating its spirit of aesthetic daring and technical invention to significantly wider audiences. For example, after finishing her stint at Atelier 17, Worden Day taught at institutions in Virginia, Kentucky, Missouri, and Wyoming. Ultimately, Atelier 17 spawned an unprecedented degree of artistic experimentation with ramifications that continue to be vital today.