- Magazine Article

- Exhibitions

Rewriting History

Kerry James Marshall acknowledges the power of the black figure

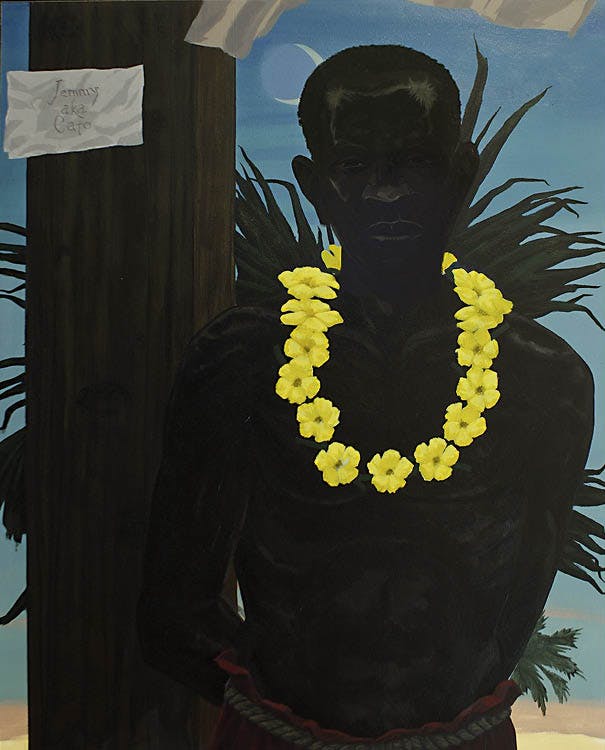

Stono Group (Jemmy aka Cato), 2012. Acrylic on PVC; 73.7 x 61 x 7.6 cm

Over the past three decades, Kerry James Marshall has intertwined the legacies of Western painting and modern-day art movements to explore the presence and absence of black people throughout art history. Part of the inaugural edition of FRONT International, Kerry James Marshall: Works on Paper allows visitors to experience Marshall’s work and processes on an intimate level through a monumental 12-panel woodcut and a selection of preparatory sketches and drawings for his grand depictions of domestic and everyday settings.

In his work, Marshall explores political and sociological themes using traditional techniques and mediums. The 12-panel print and Satisfied Man are both woodcuts—a method of relief printing from a block of wood cut along the grain. This technique was first used in the West in the 15th century and even earlier in Japan. Marshall is known for meticulously choosing mediums that allow him to explore and connect the past and present. “The form, the style, all have an essential relationship to what I think is the message,” he says. “It has to reinforce the content.”(1) Additionally, he inserts black figures in place of white ones and acknowledges the power of the black figure through dark colors and intense facial expressions. In an effort to repopulate the history of art with black bodies, Marshall masters each medium he engages in order to create a visual rhetoric using historical methods that signify the existence of the black figure in history.

Although lesser known within Marshall’s body of work, the drawings are filled with detail and great emotion, which creates an experience different from his paintings. Some of the drawings and sketches on view in this exhibition are the preparatory studies for larger works, such as Untitled (Sofa Girl), Untitled (Club Couple), and SOB, SOB. Spanning his career, these compositions reveal the artist’s techniques and artistic approach. Untitled (Stono Drawing) can be directly related to Marshall’s Stono Group series that depicts the leader of the largest slave rebellion in the British colonies.(2) Through strategies like this, he not only inserts the black figure in history but also articulates moments when black people have contributed to it.

In the untitled 12-panel woodcut, Marshall establishes the presence of the black figure in everyday life. The genteel, homosocial setting compels one to wonder about the reason for this gathering and the nature of the men’s relationships. The grand scale of the panels makes the figures almost life size, inviting the viewer to connect with them and to create a narrative. One way to interpret the scene might be through the notion of “kinship,” a system of support in black queer communities.(3) Forms of kinship arise in response to the sociocultural and economic forces of exclusion that such communities experience. These relationships become important to people’s lives and security, offering protection, love, comfort, and bonding.

The mundane setting evokes normalcy, in line with Marshall’s goal of making the presence of black figures in art a “commonplace.”(4) Here, he challenges social constructs and deviates from the stereotypical Western presentation of black men in social settings where they have been characterized as threatening, violent, or irresponsible. Instead, these six men are engaged, composed, and relaxed. Pushing away from the historical perception of the black male, Marshall interweaves histories of art and Western representation in intricate and subtle ways, giving visibility to black figures where they were previously absent.

Cleveland Art, September/October 2018

Notes

1. Kerry James Marshall, Terrie Sultan, and Arthur Jafa, Kerry James Marshall (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2000).

2. For a chronology of historical events that have influenced Marshall’s work, see Abigail Winograd’s compilation at https://exhibitions

.mcachicago.org/kjm/index.html.

3. Marlon M. Bailey, “Performance as Intravention: Ballroom Culture and the Politics of HIV/AIDS in Detroit,” Souls 11, no. 3 (1990): 253–74.

4. “MCA Talk: Kerry James Marshall,” Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, YouTube video, last modified 2018, accessed July 1, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BxPJsCiNMno.